Featured image source: Donald Trung Quoc Don (Chữ Hán: 徵國單) – Wikimedia Commons

I had to write a 650–1000-word memoir for my English 10A class. Here it is:

Short Wave

One summer, my family and I went to visit Hong Kong and perform the duties of Chinese-Americans visiting their families back home. We brought gifts of See’s candies and Polo shirts, ate fancy food with relatives numerous times (often in the same restaurant), and visited wet markets with their exotic fruits and shellfish sold by the catty (a mass unit equal to 1-1/3 pounds). We went hiking and saw enormous spiders on webs stretched between the trees above the trail, then crawled through a narrow tunnel used as an air-raid shelter to access a World War II-era gun battery. Rather than cookies, our grandparents prepared sweet soups with medicinal herbs and plates of fruit. Our relatives never talked about politics and had a very peaceful relationship with each other. We bought souvenirs: my brother got a jade cicada, and I got a steelyard scale.

On 6/4 (the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre [CENSORED BY CHINESE GOVERNMENT]), we visited the apartment of my paternal grandparents, located in a high building from which the thin smokestacks of Lamma Island Power Station, 5½ kilometers away across the water, could be seen. We sat on a narrow rosewood sofa-bench while porcelain statues of the three deities “fuk” (luck, represented by a man carrying a child), “luk” (prosperity, a government official with a fancy hat), and “sau” (longevity, an old man with a bulbous forehead and a walking stick) stared down from a wall-mounted ledge. In a touch of modernity, they were placed left to right in the Western reading direction, instead of the traditional Chinese right to left. As the television showed China’s astronauts from the Shenzhou 15 mission landing safely back on earth, we discussed how Chinese TV only reported on U.S. mass shootings while American media only reported on Chinese human rights abuses.

Our gracefully-aged grandmother gave us bits of wisdom, recounting stories of when she arrived in Hong Kong and lived alone as a teenager. “When I was younger, I lived alone. Every morning, I’d have to get up and make porridge for breakfast before school, and if I didn’t, I would be very hungry and unable to focus during classes,” she said.

My brother and I nodded, receiving but not quite understanding the message.

“My landlady, who had been abandoned by her husband, didn’t allow men on the property. So when I brought my boyfriend, your grandfather, she kicked me out and we had to find someplace else to live. That’s why you must never rent. Buy a house, then move into a nicer one if you have the money.”

“You see, this is the way she grew up. That’s why your grandmother says these things to you guys,” observed my dad. She was born in Chiuchow (mainland China) in the mid ‘40s, moved with her family to Hong Kong, then was left behind as an “anchor” when they immigrated to Thailand.

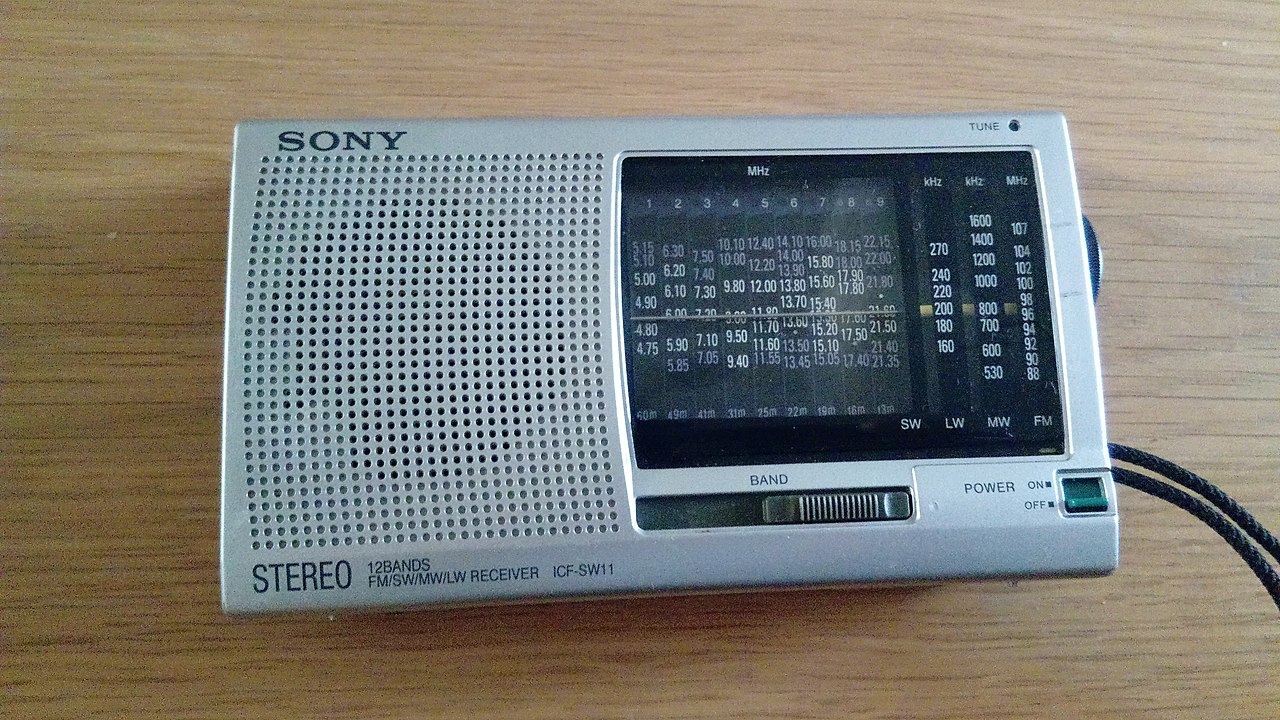

At some point, my brother and I noticed that they still had a Sony ICF-SW22 radio we’d seen when we visited them seven years ago. Unfortunately, the tuning knob no longer moved the frequency indicator and the radio couldn’t be turned on, so I asked to try and fix it. My grandparents, being handy folk (most Hong Kongers are great consumerists who rarely fix things), had some miniature screwdrivers on hand, so I set to work right away and quickly took it apart with the help of some pliers for the more stubborn screws.

The radio, like other devices of the same era, emitted a distinct musty smell resulting from the chemicals used to manufacture the circuit board. In addition, 30 years’ worth of dust compacted into little crevasses was suddenly liberated, falling on the table in little clumps. Bits of grease and dust had mixed into a “gummy”, which plugged all the holes of the speaker grille, and needed to be pushed out with a toothpick. Fortunately, due to the small size of Hong Kong apartments, paper towels and rubbing alcohol were within easy reach. After cleaning the insides, identifying the problem (a slipped timing belt used to drive the frequency indicator) and fixing it, I put the radio back together with some mistakes and mild under-breath cursing.

Now, as I mentioned before, my grandparents are handy folk who don’t like throwing things away. Years earlier, the first time we had encountered the radio I just fixed, my grandmother had lauded it for its usefulness despite its age, so I shouldn’t have been surprised when she took out a bag with two more broken radios inside. One played too soft, even with the volume cranked up, and I spent some time looking for a repair manual on my phone. The other didn’t play any sound at all. I was able to barely improve the first by twisting around an adjustment screw, but had no idea what to do with the other.

I wish I could say that I experienced a rush of emotions and felt a deep connection to my grandparents, but the truth is that I’m not a particularly emotional or sentimental person. The entire point of this story is that there were some radios, and I tried to repair them. My grandparents encouraged me to pick up good habits, at the same time supplying something to satisfy my interests. Normal grandparents give toys; mine gave me a broken radio and tools to fix it. (And money in the form of red envelopes; much more practical than toys.)

A month or two ago, they messaged us on WhatsApp, telling us they had taken the radio to a friend and had it fixed for free. The problem? A broken speaker. Oh well… for some things you just need the experience to tell what is most likely wrong.