When a piece of dried clay is heated sufficiently, the water that is chemically bound to it is irreversibly driven off, and the clay particles bond covalently to each other. After this, the clay will no longer return to the plastic state if it gets wet.

As it turns out, the temperature needed to dehydrate clays can be significantly lower than their firing temperature. According to this paper, it is between 400 °C and 600 °C for kaolins, but even lower for smectites — from 200 °C to 300 °C. Since the clay from my backyard is smectic, I was able to try dehydrating it in a toaster oven.

What I Did

Chunks of dried clay, purified by levigation, were ground into very fine powder using a food grinder and sieved to remove larger pieces that were not completely pulverized. The powder was placed in a stainless-steel bowl.

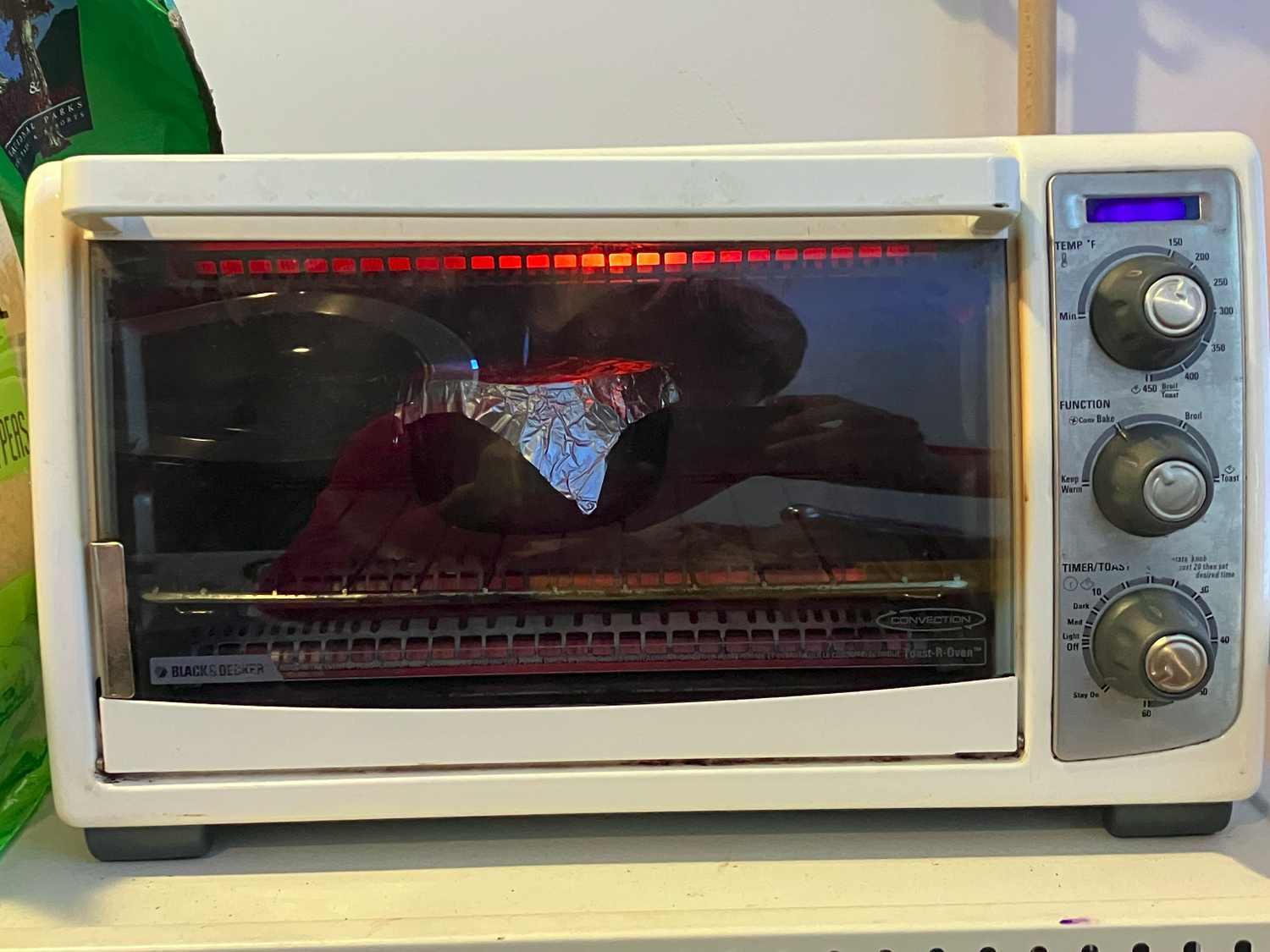

First, the toaster oven was set to 150 °F (66 °C) and the convection fan turned on to dry the clay. I’ve found in the past that radiant heat from the quartz elements can heat objects far beyond the set temperature (since the thermostat just measures the wall’s temperature), so the bowl was covered with aluminium foil with holes punched in it to prevent this. After drying overnight, the mass of the powder was reduced from 132.9 g to 124.7 g, a loss of 6.1%. Drying for an hour more only reduced the mass by a further 0.2 g (which is around the precision of my scale), so the drying process was deemed more or less complete. I also used an infrared thermometer to measure the actual temperature of the clay during the drying process, which was about 84 °C.

Then, the oven was set at 450 °F (232 °C), the aluminium foil removed, and the convection fan kept on. After 1 hour, the clay’s mass was reduced to 114.1 g, a loss of 14.1% compared to the initial mass. After 2 hours, it was 112.7 g (-15.2%), and after 3 hours it was 112.6 g (-15.3%). The clay’s actual temperature was measured at 250 °C.

I also tried putting the bowl on a kitchen hot plate set at the maximum temperature, which reduced the clay’s mass to 112.2 g (-15.6%).

To measure the clay’s weight at various stages of drying, I just weighed the bowl while it was hot using a kitchen scale, putting a piece of corrugated cardboard on the platform to prevent the hot bowl from directly touching it. It is generally not recommended to weigh hot objects because they produce convection currents that affect the reading; in Chemical Manipulation, Michael Faraday says that “a silver capsule, weighing 600 grains [38.88 g] when cold, appeared to weigh less by seven tenths of a grain [0.05 g] when heated by a spirit lamp, and again placed in the scale” (38). Seeing as my stainless-steel bowl weighs 66.8 g (stainless steel has about 70 or 80% the density of silver), I think it’s fair to say that its weight loss due to convection is within an order of magnitude of Faraday’s; supposing 0.5 g are lost (which is a pretty worst-case scenario), that would only affect my results by 0.5 g / 132.9 g = 0.4%.

Whereas the clay was a light gray color initially, it became dark brown after dehydration.

After the clay cooled for about 2 hours, it returned to a mass of 113.1 g (-14.9%). Over the next three days, it gained another 4.1 g of mass, getting to 117.2 (-11.8%) g. I’d guess this is due to some minerals re-absorbing moisture (or CO2, which can also be driven off at high temperatures) from the atmosphere. I also tried mixing a bit of dehydrated clay with water, and letting it dry again. The clay powder did become somewhat suspended in the water, and dried into a bit of a “puck” much like normal clay, but the puck was really crumbly and could easily be crushed into powder again. There was also some unidentified residue on top of the clay

Possible Uses

Digitalfire says that “calcination” (which is similar to the dehydration process I’ve described here, but occurs at higher temperatures) is used to reduce the shrinkage of glazes, allowing more clay to be added without adverse effects. I might do something similar for my DIY greensand, which relies on a high clay content to fill the voids between the very coarse sand particles, also making the greensand stickier and more compressible. The dehydrated clay powder would still fine enough to fill gaps in the sand, but wouldn’t contribute to the stickiness and compressibility, which would make patterns easier to remove. It might also be useful addition to core sand, which uses binders like oil and dextrin instead of clay, and consequently must be very fine.

Having an easily available fine powder might also allow me to make my own investment plaster. I tried using just plaster of Paris in the past, but it shrank and lost significant strength after the burnout process. Commercial investment plasters seem to made of 25–50% Plaster of Paris (calcium sulfate hemihydrate) mixed with silica flour or cristobalite and a small percentage of “additives”, so I might try mixing this powder into my plaster of Paris and casting something with it. An alternative powder for this purpose could be diatomaceous earth, which costs about $4/kg ($2/lb) and is available at hardware stores. (Side note: my previous failure with plaster of Paris might also be caused by having too much water in the plaster mix. I didn’t really measure it out precisely, I just added plaster to the water until no more would go in.)